A middle way (2018)

My father’s closest friend was his brother Joe. They both had beards, and they both wore tweed coats beneath their beards. Here they posed for their sister Ruth.

My father plays the cocky younger brother, holding his lapels, while Joe shows the pride and pleasure he took in him—the pride and pleasure an older brother feels about one who followed his footsteps. Joe helped him find a way to live the values in their family, most especially their mother’s values, without entering the ministry. A middle way.

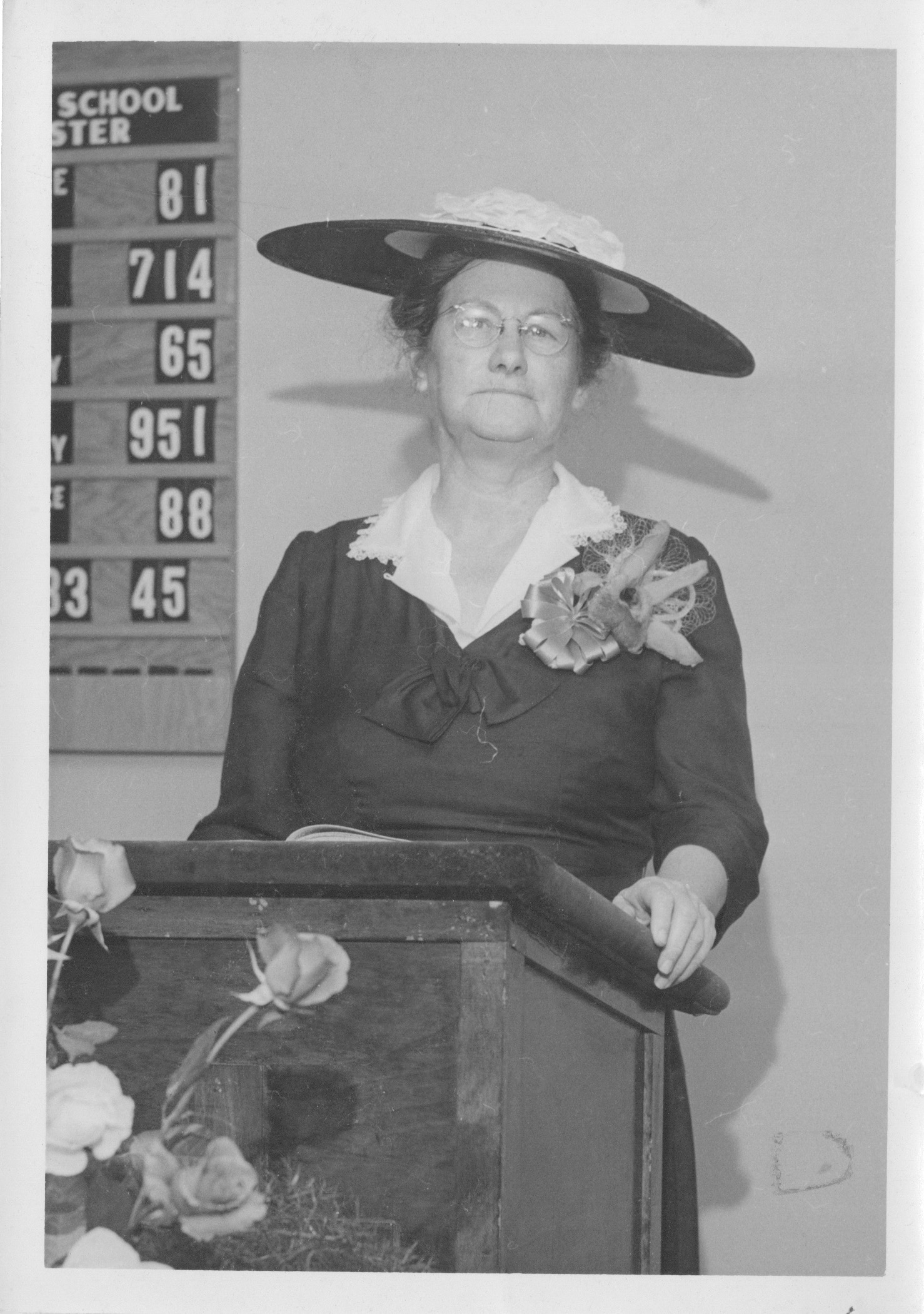

“My father would preach Sunday morning,” Joe remembered. Their father’s preaching was half a sermon and half a lecture. “But my mother would really preach Sunday night.”

She reached people. They felt she had found them, both their longing and their pain. She had suffered tragedy in her own life—a little sister burned to death while in her care, a brother who died of tuberculosis when they were teenagers, near blindness as a young woman—and she wanted to help with the sufferings of others. A Sunday sermon could only help so much. During the week, she visited with the congregation. Each struggle was a unique struggle, each pain a unique pain. It all needed to be said. It all needed to be heard. What has happened in your life to draw you toward God? What memories cause you the most pain? Was there anger between you and your mother? between you and your father? Where’s the joy in your marriage and where’s the sadness?

She expected all her sons to become preachers. She expected both her daughters to marry preachers. When Joe was four or five, he asked her if it wouldn’t be all right just to be a farmer and a Sunday school superintendent. This was a story she told about him, laughing, for years afterward. But the family did divide between the children who said yes to faith and the children who couldn’t say yes or no. Years before my father did, Joe found himself suspended between yes and no.

At seventeen, Joe thought he might resolve this tension if he read the Bible straight through, from beginning to end. He was in the Navy. They were preparing to go to sea. He needed a Bible small enough to stow in his sea bag. In the library at the base, he found a high shelf full of small bibles. He stared up at them. “I can steal one,” he thought. The thought shocked him. Then he pulled one down and opened it randomly. The chapter was Proverbs and this was the verse: “Men do not despise a thief, if he steals to satisfy his soul when he is hungry.”

He stole it. But he never read it straight through. He returned from the service and lived at home while he went to college, satisfying his inner hunger with literature and philosophy and eventually Freud. My father was ten or eleven when he returned. He spent a lot of time in Joe’s attic room. I picture Joe at a desk and him lying on the bed—a little taller and then a lot taller as each year passed.

It must have been hard for the family to let my father go to Chicago. His older brother Tim, who was already preaching, called it a mistake. How could they keep Clint in the church after he left the church community? And Clint came home from college smoking. Eighteen now, he spent the summer in the attic room that Joe had in college. He used to smoke out an open window and hide the ashtray. But one night the ashtray was full. He found a large manila envelope discarded downstairs. He started emptying the ashtray into that and then hiding them both until one night the envelope was full. He carried it downstairs but realized his mother would find it in the household trash. He walked outside. There were no public trashcans to be found. He came around the block and finally in a desperate, guilty panic dropped it into a mailbox. Except the mailbox was in front of his house. And the envelope was addressed to his mother.

He hid the evidence from his mother and then sent it to her, like Freud’s idea that there are no accidents. His mother saw all this. She saw his guilt about being different but also his need for her to understand his difference. She also saw the humor. No one else in the family missed the chance to laugh at this either, but teasing masked their sadness and concern. The Smiths grieved that Clint might be lost to the church, drawn away by Chicago and the university and the Ricketts family. He must have feared it himself. Am I going too far? Am I staying too close? He knew he needed something but didn’t know why or what it was.

Even today, my mother often wonders why she didn’t go to medical school herself. In some conversations she says, “I was never discouraged from doing that.” In others, she says she was. And of course not being discouraged differs from being encouraged—or being expected to go to medical school, as her brother was and her male cousins were. But she channeled all this, as she was encouraged and expected to do, into my father’s search for a vocation. Back in Chicago, he spent time with the man his family called Dr. Ricketts. The seriousness of purpose that characterized the Ricketts family eventually gave him structure and direction. Joe was in medical school himself now. And my father followed.

When my father first brought my mother back to Virginia, his oldest brother John and his family had never met her. They gathered at their parents’ house in Newport News and waited for Clint and Shirley to arrive from Richmond. The adults sat in the dining room. John’s five young children sat in a room near the front door, nervous about meeting a new aunt from Chicago. They still remember this glamorous woman entering the front door and then, instead of walking down the hall to meet the grownups, turning immediately into the room to meet them. Aunt Shirley soon returned with paper and pencils and sat on the floor, drawing them pictures, listening to their stories, and making up games.

At different times, I think, both families felt they had lost a child. The Ricketts felt this way during the early years of their marriage, as my mother grew ever more deeply fascinated with my father’s family. This was her adventure, and she was all in. She went to church, sang the hymns, and really listened to the sermons and the prayers. She loved how the Smiths thought about people’s lives as well as their faith. The family appreciated her effort to understand the struggles of doubt, the triumphs of faith, and conversations with God—even though she herself never felt called to the altar. “Surely Goodness” was a hymn that they sang:

"Shirley goodness and mercy shall follow me

Follow me all my days

Surely goodness and mercy shall follow me

Yeah, follow me all of the days of my life."

They sang it for her then, while smiling at Clint. They sang it for her as recently as ten years ago, when Joe and Ruth and their brother Sam were still alive.

This was the car that Clint and Shirley drove around Virginia while he finished medical school. One afternoon in Newport News, she stepped out and he gave four of John’s children a ride.

Here were the two of them arriving at Joe’s house, or leaving.

Joe had completed his residency, and he was a practicing psychiatrist now.

When Clint first studied Freud and ego psychology, it reminded him of their mother preaching. Having followed Joe into medicine, he followed him into psychiatry and later into psychoanalysis. Therapy—ministering to others in pain— was a vocation that their mother understood. And it fascinated my mother. She was as energetic and enthusiastic about psychiatry as she was about his family’s approach to religion.

I often think about how much those two men shared with each other, behind the tweed coats and the beards. Could any two people have had more in common? Their conversations were so layered, psychotherapy intermingled with their upbringing in the church—titles of hymns and verses from the Bible all mixed together with quotations from Freud and allusions to Erickson and others. It was not a friendship that anyone else could replace.