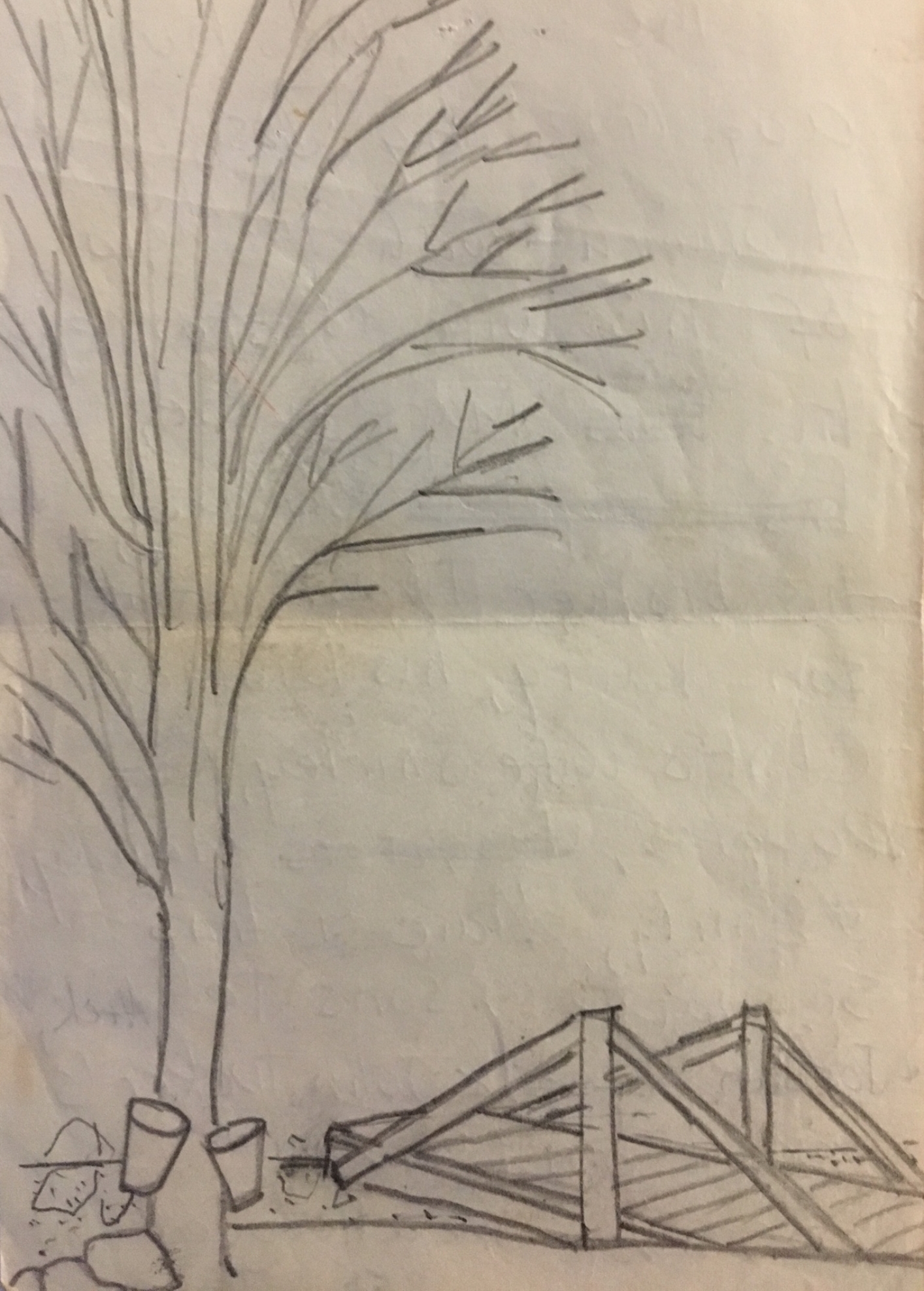

An empty drawer (2019)

In the months that followed my father’s death, my mother designed his gravestone. She drew the stream and a sugar maple beside the stream and the bridge he had built across it. She drew them from two perspectives.

And she planned the layout of the stone.

At the bottom of the stone she added these famous lines from Dylan Thomas:

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

By Thanksgiving, when my Uncle Joe’s family returned to work on the wall, the stone had been engraved and installed.

My father had requested those lines from Dylan Thomas. I think we all admired and understood the choice. They accurately captured his reaction to his illness. But it seemed to me that they also expressed how irreducibly unjust his loss felt to my mother. My own rage, at that time, remained hidden from me, but it was equal to hers. Or greater. We buried him, and built his wall, and designed his stone, and returned to family life. And all the while he continued to fade away. As each day passed and he passed further out of our lives, my mother and I became increasingly angry at each other.

On April 1, 1973, less than a month after my father died, I told my mother a dream. Because we were a psychoanalytic household, she wrote it down and kept it in a file cabinet for the next forty five years.

Daddy was here and OK.

He was working outside, the McCoys’ somewhere, when someone threw a firebomb. It missed him and I called to him to come inside, and more firebombs were thrown. One came through the window and started a small fire.

We went upstairs to find the list of emergency numbers, but couldn’t find it. The little man was making firebombs disguised as other things—he used a mold. He gave Daddy one shaped like a rose—I was suspicious of it and got rid of it.

Daddy was healthy and like always—but I was taking care of him, instead of vice versa, as it used to be. Maybe I was paying him back!

The dream was very complicated but Daddy didn’t get hurt. When the bombs came, it was like our house was in danger, not us.

You can see so much in this dream that defined me in the years that followed: My need for control, my sense of responsibility—I could take care of my father, as well as my mother—and my consciousness that our family was changing (“It was like our house was in danger, not us”). But these were thoughts and emotions my mother didn’t know I was having. Despite all my pain and confusion, I was pushing her away. “When you told me this dream,” she remembered, “what I mainly noticed was how much you weren’t sharing with me.”

Suzanne grew up with five sisters and one bathroom in a two-family. Missing all that intimacy as adults, they rent a house on Cape Cod every summer now and crowd into it. The nature of this retreat has evolved over the years, but when our kids were small they wanted time together, just sisters. I might go down for a couple of nights but would spend most of the week alone at home. And I suddenly had so much energy. I could work a full day, cook dinner and maybe mow the lawn, then stay out late at a bar with a friend, and get up earlier than usual to go into the office. We sometimes forget as parents how much we pour into our children.

When I started traveling more, Suzanne would look so exhausted when I returned. Yet for days afterward she kept doing everything herself. I called this her “frontier widow mode”—still chopping the wood and hauling the water and feeding the livestock, in addition to cooking and cleaning and caring for children. When we finally sat on the couch together, she often said, “I thought about your mother a lot when you were gone.” Our kids were about the same age then as my sisters and I when our father died. “It isn’t even all the work,” she would say. “It’s the fact that there’s no one but me to get all the emotion.”

My mother alone behind the wheel of a car—that was single parenthood. Several times a year we made the same drive south down Interstate 95 that we once made with my father. She always got lost driving toward the George Washington Bridge. There were more and more signs as we approached the bridge, crowded more closely together, and she drove more slowly than the rest of traffic so her vision was blocked by passing cars and trucks. At one point 95 seemed to end at an abrupt fork. To the left, was an exit for 278 and the Tappan Zee Bridge. On the right, 95 continued toward the George Washington Bridge. This caused her panicked self-doubt every time. Did she remember the right bridge? And then the Cross Bronx Expressway, where inevitably she took a wrong turn and then another and then another until we were driving up and down residential streets in the Bronx, while I sat in the passenger seat, still small enough so the shoulder belt crossed my face. And I remember how disappointed I felt in her for being so easily confused.

My mother used to feel almost as alone when she brought the car in for service—a woman in a garage full of dismissive, condescending men. But no hesitation or confusion this time. Here she channeled her rage. I was embarrassed, sitting in a hard plastic chair while she cross-examined them, but also impressed. She would insist on explanations, make them draw diagrams or draw them herself, and then march out into the bay to look under the hood at what they were doing. When she finally paid, she used a credit card that was still in his name, Mrs. D. Clint Smith, because the bank would have closed the account if they knew he had died.

But I believe she felt the most alone in our kitchen, when I finished searching the house for him and came to talk with her instead. Perhaps she was cooking or washing dishes. Often, she was already sitting at the table. It was a sixties-style, white oval table, like an elongated egg, that sat enclosed in a kind of glass box, overlooking our backyard. She might have her checkbook open and a pen in one hand, with a pile of bills on her right and a stack of stamped envelopes to her left. I would never admit that I wanted to talk. Sitting down and then slouching in the chair, staring straight ahead, was as much of an invitation as I could offer. She released the checkbook so it closed and laid the pen down but hesitated to start the conversation because she knew that whatever she said would be wrong.

We faced many changes that first year after he died. My best friend and Mandy’s had both lived across the street, a brother and a sister. They moved to California a few months after the funeral, which was another bereavement for us. Mandy and I also fought almost constantly. This was true before he died, but worse afterward. I felt guilty, confused, and indignant all at once about these fights, and I needed help untangling my resentments from my regrets. In June, I finished sixth grade at a small elementary school two blocks from our house, where my classmates were mostly neighbors and we all walked home for lunch. Now I took a chaotic bus ride across New Haven to a large junior high school where fistfights in the halls left blood splattered on the lockers and kids pushed you downstairs just to watch you fall. As I sat there silent, slouched, waiting for my mother to start talking, I could still imagine how he would have talked to me about these changes. He would have asked the right questions, laughed at the right time, and told a story or a joke about feeling the same way, which would have helped me name and accept what I was feeling.

If my father joined you, my mother waited for you. If he started where you were, she stood where you should be, pointing at a mark on the ground. She felt she owed us these high expectations. They were her contribution to our growing and becoming, and I imagine my children feel that this accurately describes me as well. Her love was the goals she set, and all the help she stood ready to give. But there were days or moments in a day when I couldn’t stand to be measured and judged and just wanted to be seen and heard.

I came to her, in these moments, looking for him. She wanted to help. She had helped me in so many ways for so many years, but what she offered was not sympathy but solutions. I would finally start talking. Then I would hear her defining the problem, whatever it was. I would hear her considering ways to solve the problem. But I never felt she responded to me because she didn’t respond to my emotion. Frustrated that she hadn’t responded, I would repeat what I said, but then I hadn’t heard her. Hurt that I had rejected what she had to offer, she would repeat her solution, which only made me feel more unseen and unheard. And this only made her feel more unappreciated and alone. In a matter of minutes, even seconds, I exploded in frustration and left her alone again at the table.

“I remember thinking throughout this whole period of time,” my mother remembered, “that the wrong person had left.” What made this all the more painful was how much she missed the same person. All my emotion triggered all her emotion, and she faced it all alone. In the silence after I stormed out of the kitchen, as she spread the checkbook open again and picked up the pen, I’m sure she also imagined the conversations she would have had with him. What I needed, she needed also—and more desperately because my sisters were struggling as well. She no longer had access to his depth of human understanding. He was no longer there to help her reflect on herself and her impact on us. And she felt overwhelmed, even lost, amidst the complexities of our emotions and our evolving states of mind.

Yet there we were. I was the only male left in the family. And she was the only parent. And we both kept looking to each other for what we used to find in him—like pulling a drawer that always opened empty.