A second thwack with a big hammer (2019)

I met Suzanne in an old people’s fish restaurant called Leo’s on the Upper East Side of Manhattan. She was a struggling actress. I was a struggling writer. We both waited tables. The restaurant stood on Madison Avenue, at the corner of East Seventy-Seventh Street. Dark wood and green paint defined the décor. A few mirrors and some smoked glass made it feel like a cross between a delicatessen and a saloon. It had booths and banquettes and an ornate wooden bar and a cashier’s cage where a man named Enrique used to lay two fingers against his cheek and ask, “How are you, Douglas?” drawing out the syllables of my name and batting his eyelashes before he slid the check from my hand. Older people came for early dinner at four thirty. The middle aged arrived later in the evening. They all seemed to come just to fight with the restaurant, as if dinner were a competition they either won or lost. The price was never right and neither was the food, nor the service.

The demanding, demeaning customers frustrated me, and I couldn’t always avoid responding. A tall, gaunt man named Michael managed the front of the house. One night, after the kitchen closed, he called me over as he adjusted the spacing between the table and the banquettes in each booth. There had been a confrontation. The customer had complained.

“Doug!” He slammed the table square against the wall. “You do not—” He slammed one end of a banquette away from the table. “—belong—” He slammed the other end toward the table. “— in this profession.”

For years afterward, Suzanne’s stress dream involved the six-top overlooking Madison Avenue and an assistant manager named Jesse, who was about as tall as a sixth grader and wore a suit with the sleeves and the pants too long, as if he still expected to grow. In the dream customers insulted her and Jesse harassed her, back and forth to the kitchen, until she picked him up over her head and tossed him onto the center of the table.

We did all the checks by hand, and they docked us for any math mistakes, even though the managers kept two separate sets of books—one they showed the owner and another that reflected how much they were stealing from him.

A year earlier I had been at Oxford, studying philosophy and reading Latin and Greek.

Although I walked to work dreading the start of my shift—chin dropping, shoulders drooping, and fists driving deeper into my pockets the closer I came to the restaurant—once I passed through the front door, said hello to Enrique and the bartender behind him, there was nothing but the work for me until it was done. Two stations held plates, glasses, and flatware. One stood outside the kitchen. The other stood in the middle of the dining room. Suzanne and I didn’t talk to each other until some busy night when we ended up together in one of these stations, and I started complaining about how the flatware drawer was organized differently in each. Forks were on the left of the drawer outside the kitchen but on the right in the dining room. It would be more efficient if we always reached in the same place for the same utensil. She couldn’t have cared less.

“Well, you know what Emerson said,” she told me kind of slyly, watching for my reaction. “‘Consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds.’”

I laughed. It was a relief to hear someone mention a book. Then I corrected her. “What he actually said was, ‘A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds.’ So the question is whether it would be foolish to reorganize the flatware.”

As she has done so often since, Suzanne let silence be her answer to that.

Maybe a week or so later, when I arrived early for an evening shift, I found her in the empty dining room reading. She was reading Persuasion. She claims I patted her head. We started talking that night about Jane Austen’s novels, where courtship was the vestibule between childhood and adulthood and where marriage was a choice that defined the rest of someone’s life. Suzanne and I both stood in that same vestibule then. What were the choices that would define the rest of our lives? We knew it wasn’t marriage alone.

The cook, whose name was also Michael, lived almost two hours upstate. He commuted in a Camaro and cowboy boots and fought constantly with the managers and the owner. They usually fought in the afternoon, before dinner started. While calming down after one of these fights, he often reflected on the effort life required.

“I swear to god, you two—” Suzanne and I were standing, shoulders touching, near the sinks at one end of the kitchen. “I swear to god, if I had known when I was in kindergarten that I would have to go to school for twelve years and then go to college for four years and then work for the rest of my life—I would have killed myself right then.”

“At five years old?” I asked him.

“At five years old,” he repeated, turning back to a pot boiling on the stove and a question from a prep cook about how to cut a potato.

Every few months, payout on the New York State Lottery would reach some astronomical number, and everyone at Leo’s would buy a stack of tickets together. As the drawing approached, the entire staff would believe that life could be magically solved. Every time he passed me back a check, Enrique would whisper in his heavy Puerto Rican accent, “Tomorrow, Douglas . . . no more Leo’s.” The bartender would say it as he filled our drink orders, the cooks as they put plates up in the window, and the busboys as they cleared the tables. Suzanne and I would laugh at the frenzy, sharing a meal together at the end of the night.

“Are you working tomorrow?”

“No. Remember? No more Leo’s.”

Leaning against the back wall of that restaurant, waiting for the dining room to fill up or watching people finish their meals, we talked about the directions a life could take. Suzanne told me about her family in Boston, all her many sisters, and how her parents expected college for their girls yet also expected them to leave home in a “white dress or a box.” They were frustrated she had moved to New York. She had moved there with her sister Carol and then stalled out in restaurants. She wasn’t auditioning and didn’t know what else she wanted to do. Questions kept crashing in on her. What is the point of my life? What is my purpose? Neither of us understood then how incremental the answers to these questions were. Point and purpose is not delivered to you all at once. It is not a revelation but an aggregation. You find it by making a few big decisions—and thousands upon thousands of small ones.

And that was the beginning of our marriage. We were not married all at once but more married every year, until our wedding and then beyond it. Like point and purpose, a few big decisions built our marriage and then thousands upon thousands of small ones. She doesn’t like the outdoors the way I do. At the farm, the kids and I can spend entire weekends muddy and wet and cold while Suzanne might only be outside for the time it takes to walk from the car on Friday night and back again on Sunday. Inside time was her alone time, reading and crocheting and catching up on television. We thought we might like gardening together, and we do—sort of, although Suzanne thinks about flowers as form and color she is arranging in a space. She never can remember what will actually grow where. And I am far too impatient. We have always shared what we first shared in that restaurant, a pleasure in people and what people produce—books, music, movies, and art. But we have only ever truly shared one hobby, raising children.

We are still learning to live with each other. That is what sustains a relationship: The willingness to do the work of adjusting and changing. Now we struggle to adjust to a disease that still kills most of the people who have it. When I was first admitted to the hospital, eighty to ninety percent of my bone marrow was filled with leukemia. I am now down to twenty percent, but no one knows whether it will continue to decrease or start increasing again. Dr. Duggan performed the Day 28 biopsy, communicated the results, explained the next round of chemo, and then ended her week on service in the unit, and was replaced by another doctor.

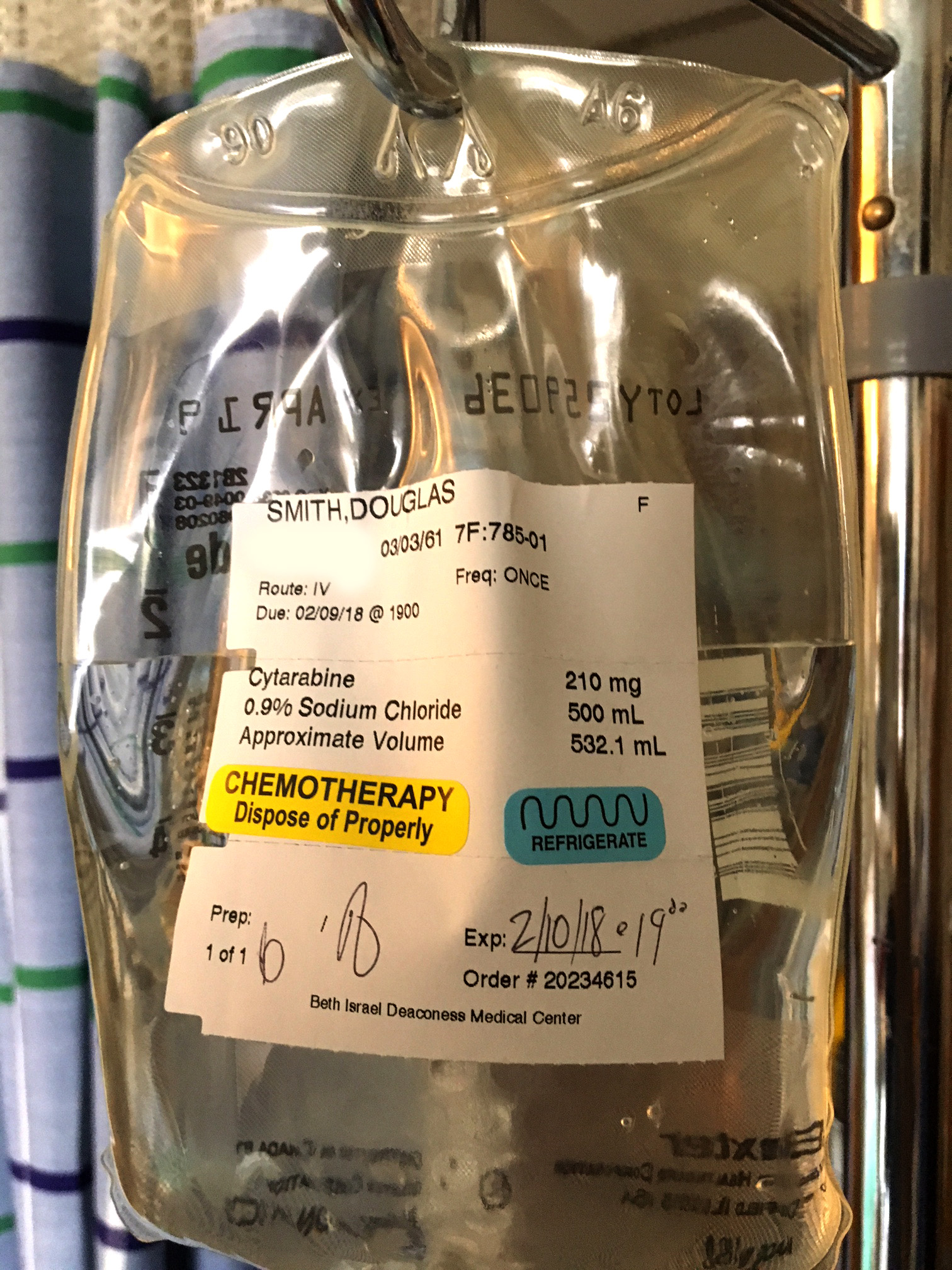

Nurses work in pairs to start the chemo. They do this to avoid mistakes. They come rustling through my door, wearing stiff paper gowns and carrying a bag of tubes and a bag of chemo like groceries. The bags drop onto the table, and they follow a protocol.

One of them stands at the computer.

The other holds my wrist at the bedside and reads my bracelet. “Looking at the bracelet, I have Douglas Smith. S-M-I-T-H.”

The nurse at the computer confirms my name.

Then the nurse at my wrist reads my medical number and asks me to give my date of birth.

“March 3, 1961,” I say.

“Your birthday’s in a month!” she says cheerfully. It is now February. Then she drops my wrist and inspects the bag of chemo on the table. “I have Cytarabine for Douglas Smith, which expires tomorrow at 8:21 AM.”

The nurse at the computer confirms the drug. She reads how many milligrams and how long the administration will last. Then they discuss the rate at which she will set the pump on my pole. They drape a special paper across my chest so the chemo doesn’t burn my skin if it spills and then start pumping the poison into my bloodstream.

During chemo, I feel like a bag myself—a sack of organic activity. I am my numbers. Blood pressure. Blood oxygen. Temperature. Weight. And all the ways they count my blood: the complete count, the differential, red blood cell morphology, basic coagulation, renal and glucose, enzyme and bilirubin, and blood chemistry. I feel formless, almost deboned, as if the inner skeleton of my history and my relationships have been removed. I am no longer who I worked so hard to become. And the question keeps forming in my mind, What if this time I am not cured either?

Everyone in the hospital knocks before they enter my room. The doctors knock. So do all the nurses and the technicians and the people who clean my room. All my visitors also knock. Even my children knock. The only exception is Suzanne. It doesn’t even occur to her. “My husband is in there,” she thinks, and just walks in. I find it comforting.

She brings Rosalind and Caleb on Saturdays and Sundays. She doesn’t come Tuesdays, Wednesdays, or Thursdays. But on either side of the weekend, on Fridays and Mondays, she comes by herself, usually in the afternoon. We lie together on my bed, arms around each other, just talking—although she always jumps up when the nurse knocks, like we were teenagers caught on the couch.

“We never sit still like this together anymore,” I say, “and just talk.”

“Well, that’s not my fault,” is her answer. “You’re the one who always has to get up and go do something.”

Across all these years, the pressure of those thousands upon thousands of small decisions has compressed our conversations into a formula. State a problem or grievance. Define it. Debate it, and try not to argue. Then agree on a solution, hopefully not after too many weeks or months. But talking here is different now because we have so much time to fill.

“I cleaned up our room,” Suzanne tells me one day. “I got rid of my piles so it doesn’t look like the place a depressed hermit sleeps anymore.”

“That sounds pretty good.”

“I even opened the shades.”

I have always needed help with acceptance. It is particularly hard to accept what has been happening to me. I keep trying to list the benefits of my illness. What is some good all this has done? Lying here like this, staring together at the blank television high on the wall or the half fridge beneath it or the rack of masks and gloves above a red biohazard trashcan, it feels like talking at Leo’s again. And I think we both had forgotten what that felt like.