Counting down to Day 28 (2019)

Suzanne grew up in Saint Gregory’s parish in Dorchester, a working class neighborhood of Boston. Saint Gregory’s stood down the hill from their house, next to a large CVS Pharmacy. Each Sunday, her mother and father went to an early mass. Suzanne chose a later mass. She dressed up, drove down the hill, and parked at Saint Gregory’s. Then she walked next door to read magazines in CVS until mass ended, when she joined the crowd coming out of the church. She called this “going to Saint CVS.” This is Suzanne. She accepts a compromise and sets a boundary: You can make me leave the house for church, but you can’t make me step inside it.

We compromised about our wedding. One of my father’s preacher brothers could marry us in a Protestant church if we agreed to complete the steps necessary for the Catholic Church to recognize our marriage. We applied to the Archdiocese of Boston for a dispensation called “disparity of cult” because I had never been baptized. I signed a legal agreement promising to raise our children Catholic. And we registered for Pre-Cana classes led by a priest. The marriage preparation classes were two Saturdays in a row. I leaned against Suzanne, squirming and sighing and rolling my eyes as we suffered scripted platitudes delivered by someone who had never been married. She sat quietly, patting my hand. This was the deal we had made, the line she had drawn, and she accepted it.

In the last hour of the last day, the priest sat us together on the floor, back to back, and gave us paper and colored markers. He asked us each to draw a picture of what we expected married life to be like. Folding my arms, I refused to participate, but I heard Suzanne drawing behind me. When we turned to face each other, she had drawn the edge of a garden, a driveway, and a kitchen. You could see a car in the driveway and a large kitchen window. She was getting out of the car, coming home from work. I stood behind the kitchen window, cooking dinner.

This is how a marriage evolves. What we do for each other becomes part of the intimacy of marriage. Emptying the dishwasher, sorting the mail, remembering to call the electrician or renew the registration on the car signals commitment. It’s a way of being present for each other. Lying in the dark at the hospital, listening to my IV pumps, I think about how intertwined we have become. When Suzanne is away, I hate making the bed. It feels sad and lonely and I never do a good job. The blankets all hang unevenly and I can never quite get the bedspread smooth. I feel the same way about washing the towels in the bathroom, or filling the hand soap containers, or the way the furniture in the living room is never in quite the right place when she isn’t there but I don’t really know what the right place is. And she feels the same way about my cooking.

The hospital shift changes at seven in the morning. My nurse today stands at the computer, with her back to me, and empties her pockets onto the tray above the keyboard. She has brought my morning pills. She has also brought a bag of saline solution, which lies flopped on the table, along with a coil of IV tubing, near where Rosalind leaves her gifts for me. The pills are still in their wrappers. She pops them out one by one into a little plastic cup, which she then carries to me, between her thumb and forefinger, along with a bottle of water. I have to drink bottled water, because of the risk of infection, and she opens it for me, as if I were too weak to twist off the cap.

“Any pain?”

If I say yes, I have to rank my pain on a scale of 0-10. There is a sign in the room to help me.

But I never know what to say. Suzanne, who broke her ankle badly as a teenager and gave birth to three children, would have such a different scale than I do.

“Any distress?”

“No.” Otherwise, I’d have to give that a number also.

She checks a box onscreen. “Fevers, shaking, chills?”

I think for a moment. “No.”

“Night sweats?”

“Yes.”

“How bad?”

“They changed my sheets and gave me a new gown at two in the morning.”

“Okay. Headaches? Any headaches? No?”

“No.”

“Coughing, chest pressure, sore throat?”

“No.”

“Abdominal pain? nausea? vomiting? diarrhea?”

“No.”

“When was your last bowel movement?”

“This morning.”

“Hard or soft?” she asks.

“Soft.”

She is still checking boxes. “Formed or unformed?”

“Unformed.”

All my empty water bottles stand in a cluster on top of the refrigerator, just below the computer keyboard. She records each one and then flicks it into the trashcan. No recycling here.

“Do you have urine in the bathroom?”

“Yes.”

I listen to her pour out the bottle and flush the toilet. Then she records that. Fluids in and fluids out. “I forgot to ask about shortness of breath. Do you have any shortness of breath?”

“Yes. But not when I am sitting still. Just when I am walking.”

“How would you rank your shortness of breath on a scale of 1-10?”

“I don’t know.” I imagine myself suffocating. That must be a 10 in shortness of breath. “Maybe a 3?”

Suzanne almost never asks what I am cooking until she is setting the table, and she never complains when I cook something she doesn’t particularly like. She does cook sometimes. She is actually a good cook. But she isn’t cooking now, and I worry about what my family is eating.

Everyone we know—friends, family, colleagues—wants to help her. They want to bring her food, but she isn’t answering calls and texts. Four of her five sisters live within a few miles of our house. When they reach out, she doesn’t answer them either.

“Are you accepting help?” I keep asking when we talk at night. “You need to accept help.”

She tries not to answer me. If I ask her several times, she might finally say, “Not really.”

Her sister Carol and my sister Mandy tried to organize a schedule, but they didn’t know what nights she needed dinner, and Suzanne wouldn’t answer them. Carol finally called Isabelle, who stood between Suzanne and the television, still holding the phone against her ear, and asked when she needed meals. Isabelle relayed her answers. People also sent gift certificates for takeout food, but Suzanne doesn’t like to use them without me, so they have just collected on her desk or in her email.

There are many things Suzanne does for me, but this is what I do for her. When she withdraws, I go find her. She is deep inside her tunnel and her bunker now, locked inside that soundproof room, and I am not able to follow her down there. Sometimes all people see on the surface of the earth is her hologram. Every once in a while she rises up and inhabits her hologram, but she quickly retreats underground. The kids seek her out—they climb down into her tunnel and knock on her door. But it takes so much effort to reach her there. The kids need her present. They need her watching, listening, asking questions. She isn’t doing much of that right now. So I worry about them also.

“Do you remember, Mom?” Isabelle asks. “Always say yes to spending time with friends.” Suzanne has used that phrase with her. It sounds like something they both heard on a children’s show.

“You need to go out,” her friend Amy tells her one night. They are sitting together in the high school auditorium, waiting for a concert to start. Another friend sits with them. “We need to take you out to dinner.”

Suzanne says yes. But as they start talking about when, she has a reason why every night that works for them won’t work for her.

Amy starts laughing at her. “Do you need me to make you do this? Do you need me to force you to go out?”

Suzanne is smiling.

“Do you need me to climb up that trellis on your front porch and come in through a window? And drag you down the stairs and out to the car?”

Suzanne says yes she probably does need that.

This is the question I keep asking my doctors. I ask it almost every day. “When can I go home?”

“Sometime around Day 28,” is the answer I keep getting, “though we can’t tell you for sure.”

But I am already counting. Today is Day 18, a Saturday. “I am more than halfway there,” I blurt out during rounds.

“We talked about this. Remember?” Dr. Dreier asks. “Everyone is different in terms of when their blood counts recover. It probably won’t be exactly Day 28.”

My nurse stays after the doctors leave. She watches the door close behind them. “Day 28 wasn’t like a promise, okay?” she says. “You understand that, don’t you? We can’t promise you a particular day.”

“Yes, I know,” I say. “I understand.”

But when the door closes behind her, I am counting again. I have one more weekend. Next Saturday will be Day 25 and next Sunday will be Day 26. Day 28 will be Tuesday, January 30.

They draw my blood at midnight. Every morning, a nurse writes my blood counts on a dirty whiteboard.

Every morning my counts are lower than the day before. The White Blood Cell count (WBC) and the Absolute Neutrophil Count (ANC) protect me from infection. Platelets (Plts) help with clotting. Hemoglobin (Hgb) carries oxygen in my blood. “All expected. It’s all expected,” Dr. Dreier says, as my numbers sink toward zero. “This is what happens after chemotherapy.” But no one is relaxed. At all. They monitor me with a certain vibrating intensity.

This vigilance has its reasons, but it also has its costs. I have no control over anything that happens on any particular day.

“Your wife was sick?” Now it’s Sunday, Day 19. A different nurse is hanging a bag on my IV pole. Her name is Sally. “Then she can’t visit.”

“What?”

Hands still above her head, Sally glances down at my face on the pillow. “I’m sorry. That’s the rule.”

“She was sick. She isn’t sick anymore.”

Sally looks like she was an athlete in college. “Did she have a fever?” She probably coaches youth teams now.

“No.”

“Abdominal pain? nausea? vomiting? diarrhea?”

“No.”

“Coughing? sneezing? sore throat?”

“Just a sniffly nose.”

“How long has she been feeling better?”

“Twenty four hours.”

“I’ll talk to the team,” she concedes. “But I know what they’ll say.” She pats my shoulder. I keep imagining her with a whistle around her neck. “Don’t let this get you down. She’ll probably be able to come tomorrow.”

“She has to work tomorrow. I won’t see her until Friday if she can’t come today.”

“I’ll ask. That’s the most I can do.”

I can’t brush my teeth with an ordinary toothbrush because my gums may start to bleed and not stop. So I have a sponge on a stick that I throw away after each use. I can’t eat food that has been uncovered because it collects bacteria from the air. So my meals arrive covered and soggy from the trapped steam. They also have a strange taste. I can’t eat salad or any vegetables that aren’t cooked. I can’t eat most kinds of fruit. Bananas I can eat, because they have a thick skin, but I can’t peel one myself because the skin carries a fungus. If I order one for breakfast, Food Service brings it separately, on a paper plate with my room number written on it. They leave the paper plate at the nurse’s station. My banana arrives peeled after someone notices it there, which is usually around lunch time.

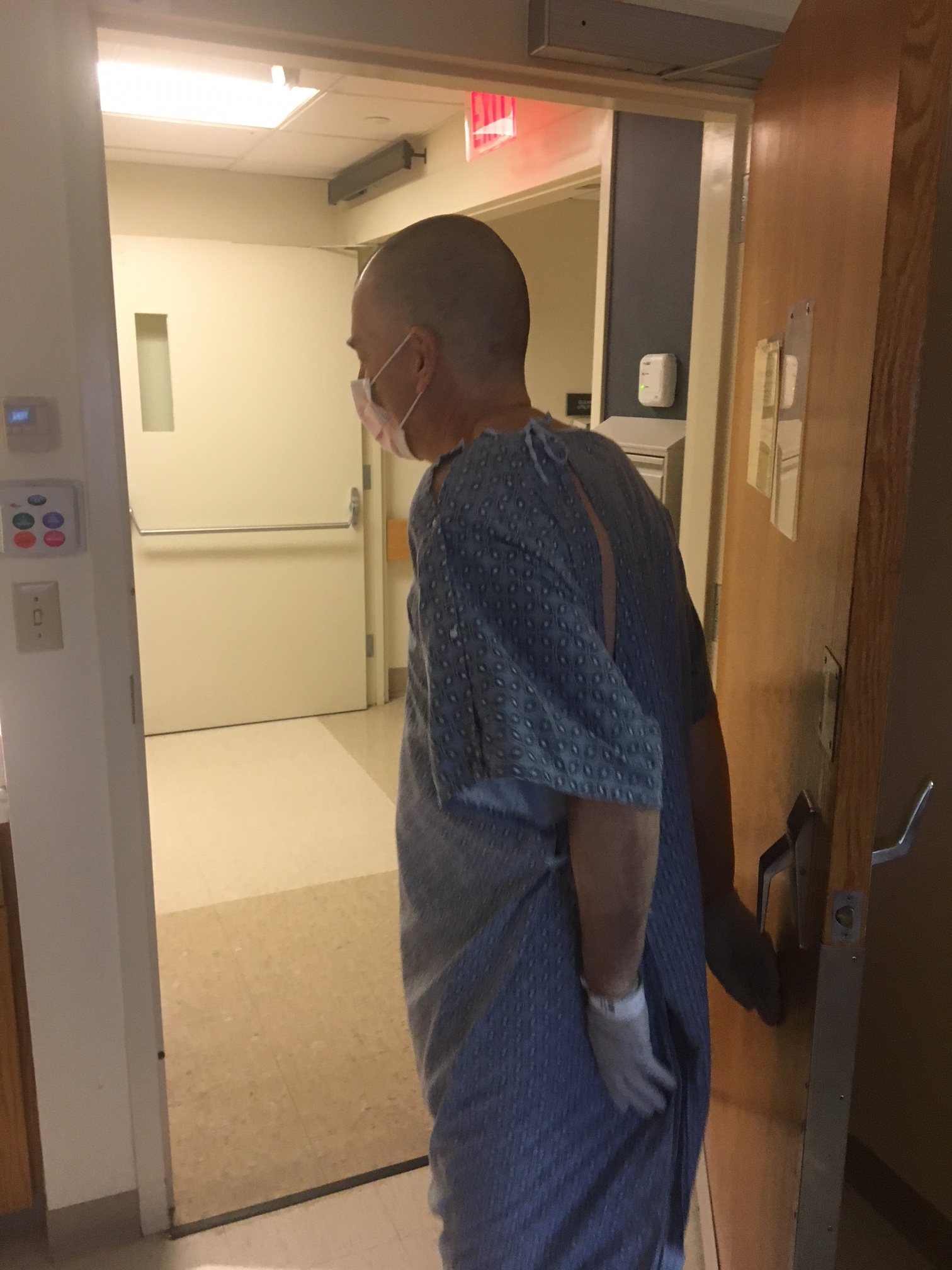

And I can’t leave my room. I am expecting to go home in ten days, but I can’t leave my room. My hair starts falling out, and I finally let them cut it off. I sit near the window, by the table. You can see the back of the door behind me.

Except for CT scans and other tests, I haven’t been allowed to leave my room since I was admitted. Getting my head shaved makes me feel even more like a prisoner.

For years Suzanne and I lived like graduate students in a kitchen with no cabinets or counters. We had a round wooden table we pulled out from the wall so we could all fit around it—a circle of matching glasses and cloth napkins, inside a circle of plates with a floral pattern, inside a circle of mismatched chairs. Everyone sat in the same place every night. When I made pasta, if the bowl of grated Romano was anything less than almost overflowing, Suzanne would warn the kids as she set it in the center of the table, “That’s all the cheese we have.” Fascinated with stories of all kinds, our children inherited her obsession with movies as well as her precise verbal memory. For years, the four of them re-enacted entire scenes—even at three Caleb remembered the dialogue, word for word, and all the facial expressions and hand gestures.

Isabelle returns to college. With Suzanne in her bunker and me in the hospital, I keep worrying that we aren’t focused enough on the kids we still have at home—who they are and what they need. I start using FaceTime to call in for dinner. Caleb puts the food on the table and Rosalind set up the computer so I am looking at just the two of them. We remodeled our kitchen last year. The round wooden table is gone.

Sometimes they show me the dog, who doesn’t recognize my voice or my image and just wants to get back down on the floor.

The first few times I call in for dinner, Rosalind and Caleb start bickering with each other as soon as the camera goes on. At first, I just listen to it. I don’t cut it short, as I would have done if I were home, and their fighting only grows worse. I keep thinking how we are all going through a lot, how calling in for dinner is a special occasion which we have to keep special, until I realize that is the opposite of what they need. They need this to feel normal. They need me to cut it short as if I were there. So after a few evenings, I do. And they seem relieved. We still talk about movies, but it is more analytical now. We talk about their classwork, friends I know and friends I don’t, Rosalind’s college applications, and Caleb’s obsession with Formula One racing.

As my blood counts finally start moving away from zero rather than toward it, I also start asking my nurses and my doctors when I can leave my room. While they measure my blood pressure, my blood oxygen level, my temperature, and my urine, while I eat my soggy food and wait for my banana to arrive, walking feels like the promise of freedom.

“A few more days,” my nurses say. “Maybe you can leave the room in a few more days.”

Then I spike a fever. They administer a battery of tests to rule out a long list of infections. And their answer changes.

“We can’t have you walking around the unit and potentially infecting other patients until we know for sure that you don’t have one of these infections.”

“But don’t those tests all take a week to come back?” I ask.

“Yes.”

“So I have to wait another week to leave my room?”

“I’m afraid so. Sorry.”

“Good news!” a nurse tells me a week later. “The results came back! You don’t have any infectious diseases.”

“So can I leave my room?”

“Yes.”

“And walk around the hall?”

There is a long pause. “Uh, I don’t think so. Let me talk to the doctors.”

The answer comes back no.

“Your blood counts are still too low,” she says.

And I am surprised. “I thought we were just waiting on the tests.”

“No, the blood counts too. What if you faint and fall? Your hemoglobin is still really low. And then if you hit your head, it might be hard to stop the bleeding. Because of your platelet levels.”

I have this moment when I feel like I am shaking my fists through the bars of my cell and bellowing in frustration. But all I say is, “Fine.”

Two days later, after a few transfusions, another nurse tells me, “Your blood counts are high enough so you can leave the room.”

“I can leave my room?” I repeat. “Today? Can I walk around the hall?”

There is a long pause. “Uh, I better check about that.”

Two hours later, she comes back with a reason why I can’t walk around the hall. This time I get stubborn and ask to talk to a doctor. Two hours after that, a doctor knocks on my door. I make my case, and he lets me leave the room and walk around the hall. A friend documents me finally opening the door myself.

And walking in the hall.

When I finish, the nurse is waiting in my room. They have forgotten about a test. I have to take it today. And I can’t leave the room again until the results come back.

But I am drawing closer and closer to Day 28.